The plight of the battery cage hen is no secret.

We’ve all seen the photos. Hens crammed into small pens, each afforded less space than a single sheet of paper. Unable to engage in natural chicken behaviors like scratching, perching, or nesting. No room to spread their wings, much less take flight.

There are around 275 million laying hens in the U.S. table egg flock. As of September 2015, more than 90 percent of those hens were in battery cage production systems, according to the United Egg Producers. That’s a lot of hens spending their entire lives in cages.

But things are about to change. Battery cage egg production is coming under fire from animal welfare groups. Groups like the Humane Society of the United States and Mercy for Animals are lobbying the food industry to adopt animal welfare practices.

Those efforts are being met with success.

In late December, fast food chain Subway announced that its 30,000 North American restaurants would use 100 percent cage-free eggs by 2025. McDonald’s made a similar pledge in September. Nestlé, the world’s largest food company, said it will go cage-free by 2020. Taco Bell set an even more ambitious timeline, vowing its 6,000 U.S. outlets would make the switch by the end of this year.

So what does this news mean for laying hens? And for the farmers who raise them? You may be surprised.

What are cage-free eggs?

When you see the term “cage-free” on an egg carton, you probably picture a flock of happy hens foraging for bugs in a grassy pasture, right? Think again. While cage-free hens may have significantly better lives than their battery cage sisters, their lives may not be as idyllic as you imagine.

Except for use of the term “certified organic,” the U.S. Department of Agriculture does not regulate egg carton labels. Instead, egg producers may participate in one of several voluntary animal welfare or industry certification programs that set standards for cage-free labeling. The specific criteria vary by program, but generally a cage-free label means:

- Hens don’t live in cages.

- Hens are provided some opportunity to nest and perch.

- Hens may be kept indoors at all times without outdoor access.

- Beak-cutting, a process to remove part of the chick’s beak, usually within days of hatching, is allowed.

Is cage-free better?

The reality for most hens in cage-free production systems is a life spent in a large barn with thousands of other hens with 1 to 1.5 square-feet of floor space each and no outdoor access. While hens have more freedom to express their natural chicken behaviors, crowded conditions lead to pecking and cannibalism, and studies have shown higher hen mortality rates in cage-free systems than in other housing systems.

The Coalition for Sustainable Egg Supply, a group made up of egg suppliers, food industry companies, academic institutions, and the American Humane Association, conducted the Laying Hen Housing Research Project, a commercial-scale study of three housing alternatives for laying hens – conventional cages, cage-free aviary, and enriched colony (a cage system with lower density than conventional cages and with access to perching, nesting, and dust-bathing). The study found each alternative had trade-offs relative to hen health and well-being.

Compared to the conventional cage system, the cage-free system was found to have the following impacts to hens:

- Worse mortality

- Substantially better behavioral freedom

- Substantially worse cannibalism and aggression

- Substantially worse keel (breast bone) damage

- Substantially better tibia/humerus (leg bone) strength

- Slightly better feather condition

Both housing systems had similar impacts on hen health and well-being with respect to the following:

- Stress physiology

- Foot condition

- Environmental comfort

- Feeding and drinking

In addition to animal welfare, researchers looked at housing system impact on four other egg production sustainability areas – food safety and quality, environment, worker health and safety, and food affordability. They found the choice of housing system had the least impact on food quality and safety. Eggs from both the conventional cage and cage-free systems were within U.S. egg quality standards.

However, compared to the conventional cages, cage-free housing was found to have the following – mostly negative – impacts on environment, worker health and safety, and food affordability:

- Slightly worse carbon footprint

- Substantially worse indoor air quality

- Slightly worse manure management

- Substantially worse particulate matter emissions

- Slightly worse natural resource use efficiency

- Substantially worse worker particulate matter exposure

- Substantially worse worker endotoxin exposure

- Slightly worse worker lung health

- Worse worker ergonomics

- Slightly better worker access to cages

- Slightly worse feed cost

- Exceptionally worse pullet cost

- Substantially worse labor cost

- Exceptionally worse capital cost

- Exceptionally worse total capital and operating cost

The Coalition’s Final Research Results Report was careful to note that the research represented a snapshot in time, assessing a single hen breed at a particular Midwestern farm in particular housing systems. Variables such as breed selection and management skills undoubtedly are important parts of the equation, and more research will be needed. But the findings underscore that a transition to cage-free eggs will not be as simple as merely releasing the hens from their cages.

A cage free aviary in Israel. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

What does cage-free mean for farmers?

Since the 1950s, large scale egg production has relied upon hens housed in cages. Cages allow farmers to produce eggs efficiently and cheaply by offering a high degree of control over the birds. Hens in cages aren’t stepping in poop or pecking one another to death. Eggs are cleaner and easier to collect. Of course, the trade off is animal welfare, and generation after generation of laying hens have spent their lives in barren cages with no room to move.

Meeting consumer demand for more humanely raised eggs will require a massive supply chain overhaul. Only about 4.5 percent of the 7 billion table eggs produced in the U.S. each month come from cage-free production systems. Meeting the timelines set by McDonald’s, which uses about 2 billion eggs a year, and other companies switching to cage-free eggs over the next decade will present considerable challenges for egg producers. Farmers will need to figure out how to produce cage-free eggs on a large scale, and they need to figure it out fast.

A significant and immediate challenge to egg producers is a fiscal one. Egg producers will need to retrofit existing barns with expensive cage-free systems that house fewer birds than conventional cages. They will need to reduce their flocks, meaning a decrease in production, or build more barns. They also will need to start over with a new generation of laying hens. (Hens that grew up cages can’t be moved mid-life to cage-free housing; their immune systems aren’t equipped for it and the pecking order would be in chaos.) Feed costs will increase because the birds will be moving more and burning more calories. Labor costs will increase, too.

Almost inevitably, a share of the increased costs will get passed down the supply chain to consumers. But farmers will bear the initial burden. And they won’t know for sure how much of the costs they will be able to transfer without impacting market demand.

Another challenge of the conversion will be the greater management effort required by cage-free housing systems. Egg producers will have to set aside more than a half century of egg production advances based around the cage. They will need to learn how to mitigate the risks of injurious pecking behavior and disease in a cage-free system. They will need to become skilled in a new production method even as the threat of avian influenza looms on the horizon.

Egg producers seem to be up for these challenges, albeit begrudgingly. Speaking at a Leadership Iowa agricultural session in Wellman, Iowa, in November, Randy Olson, Executive Director of the Iowa Poultry Association, noted that Iowa egg producers are ready to meet market demand for cage-free eggs, even as they are frustrated about decisions made in corporate boardrooms that directly impact their operations.

“I have absolute confidence that farmers care deeply about the animals they raise,” Olson said during the Nov. 6, 2015, presentation on avian influenza and other threats to productivity. “No one knows best how to care for the animals than the farmers who have the history and the legacy.”

Noting the increased costs, lower production, and higher hen mortality of cage-free egg production, Olson emphasized that producers will give consumers choices and it will be up to the consumer to decide what he or she will pay for.

What are the options for consumers?

Informed decision-making is a good thing, and knowing the truth about cage-free eggs will help you decide how to choose your eggs.

If you prioritize cost savings over all else, you have perhaps the easiest choice to make. Simply look for the lowest price tag. Understand, however, that at least for now, those cheap eggs probably will come from battery cage hens.

If you believe that cage-free housing is a humane solution for large-scale egg production, go ahead and buy those cage-free eggs. But be prepared to spend a little bit more for them, at least for now.

If you believe cage-free housing is not a humane solution and are prepared to spend even more for your eggs, look for these egg carton labels that promote higher animal welfare practices:

- Free-range: Hens have access to the outdoors, although such access may be limited and the outdoor space may be void of vegetation.

- Certified Humane Pasture-Raised or Animal Welfare Approved: Hens enjoy the most freedom and space and are provided an opportunity to forage outdoors on living vegetation.

Of course, if you want to be certain that your eggs are raised humanely, your best option may be to source them from small, local farms where you can see for yourself how the hens are being kept.

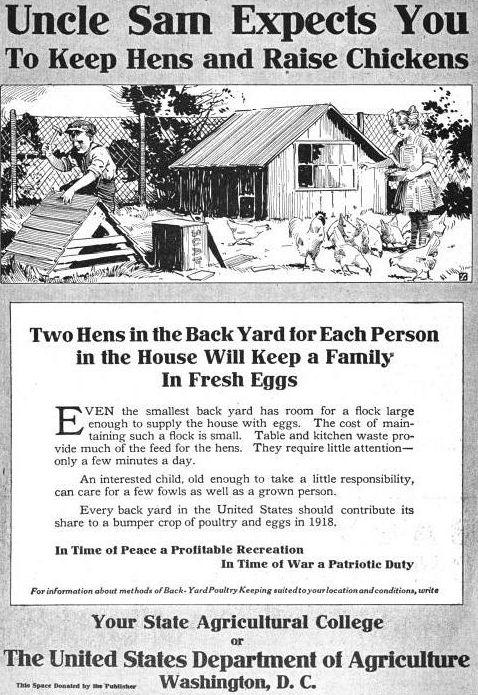

Or keep your own hens.